Climate crisis as a human crisis – facing inhumanity with ethical creativity

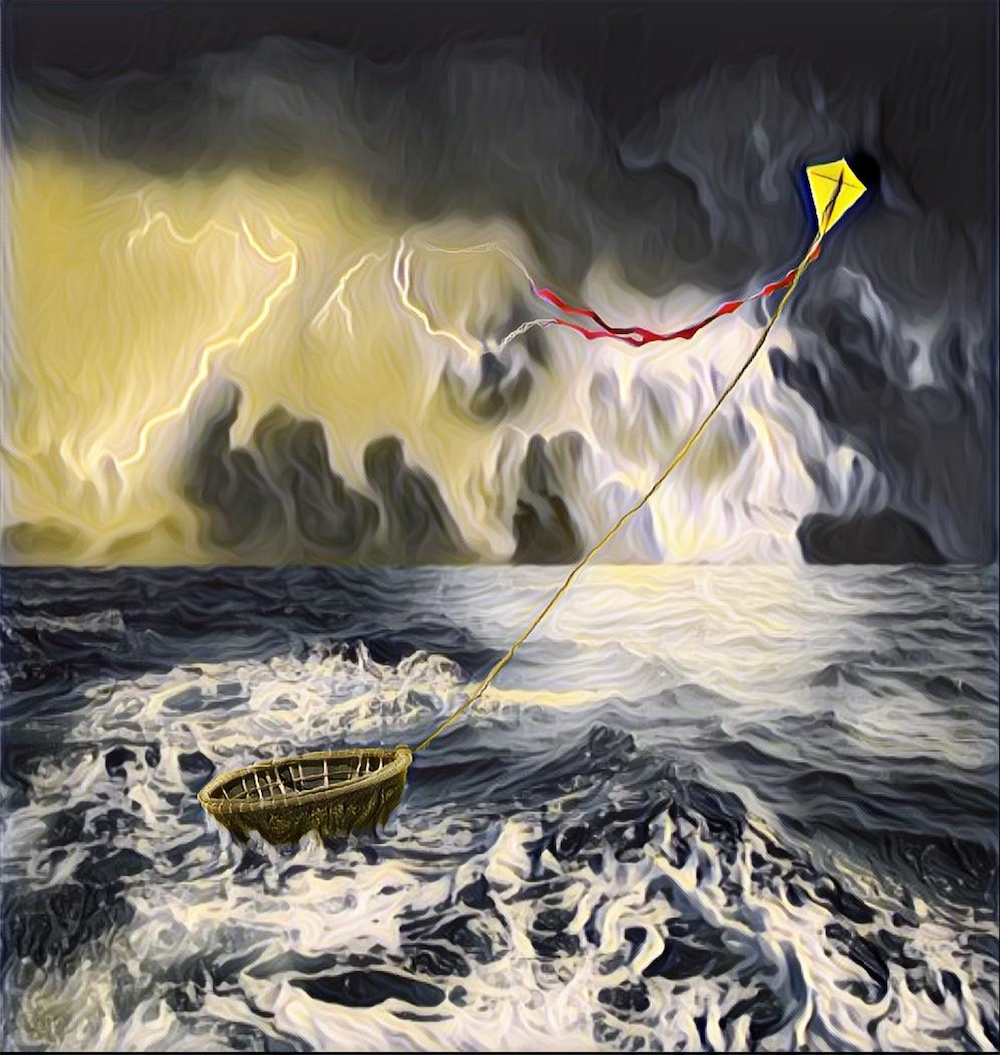

This reflection considers the fate of humanity at the intersection between the climate crisis and the migrant crisis. The international regimes of climate governance and humanitarian protection are moving in opposite directions, tearing the fabric of our shared humanity, and creating abyssal inhumanity at Europe’s borders and on the high seas.

In a striking essay ‘The Armed Lifeboat Between Glasgow and Bruzgi’, Itamar Mann contrasts the emerging international regime to control CO2 emissions with the disappearing regime protecting migrant rights:

For those who will continue to be displaced by the changing climate and its economic and health fallouts, this European lifeboat — even if increasingly less carbon-dependent — is not only revoking non-refoulement. It is preparing its guns

The figure of the ‘armed lifeboat’ replays the violence of ‘lifeboat ethics’, a project of racial-exclusionary ‘ecology’. The UN Human Rights Committee’s decision on the Teitiota v New Zealand climate refugee case (2020) illustrates the gaping distance between environmental and human protection principles: people are forced to move by disproportionate burdens of climate risk, loss and damage, yet they face impossibly high thresholds to secure protection. The political demand to ration welfare within national borders, exclude ‘Others’ within and ‘externalize’ human and environmental costs results in dehumanization on all sides.

The universal nature of human dignity and rights demands not only the protection of the planet from excess greenhouse gases, but also the extension of solidarity beyond the cynical ethics of ‘armed lifeboats’. Global solidarity requires ethical creativity, ethical imagination, and ethical know-how. Global civil society must act in coalition to foster ethical internationalism and humanity, and develop ethical creativity, imagination, and know-how, in a world order that is frequently and increasingly incompatible with internationalist and humane principles.

The 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact might present an unsatisfactory plan of action to reverse climate crisis, but at least it represents – in principle – international norms moving in the right direction. This cannot be said for refugee protection, which has moved away from established, principled international norms of protection, especially since the intensification of the ‘migrant crisis’ since 2016. Nearly two decades ago, sustainability scientist Petter Naess had already observed a waning solidarity:

Today, the willingness among decision makers in rich countries to pursue a sustainable and globally solidary development appears to have declined significantly. Instead, a cynicism or hostility against ‘the Others’ seems to gain momentum.

Such cynicism is accompanied by sociological distancing – presuming that ‘the Others’ have no faces and therefore don’t count. Climate transition involves intense polarization; therefore confrontation is unavoidable. The ‘Armed Lifeboat’ replays the cynical environmentalism of Garrett Hardin, who used ‘ecology’ in his popular essays – ‘Living on a Lifeboat’, [1974]** and ‘Tragedy of the Commons’ [1968]** as a means to pursue ‘lifeboat ethics’, an ethic opposed to welfare and immigration, and in favour of reproductive coercion and racism. Hardin ‘used the spectre of environmental destruction and ethnic conflict to promote policies that can be fairly described as fascist’.

Our world is facing an overwhelming ‘omnicrisis’. Forced displacement is growing, with 1 in 95 people forcibly displaced in 2020, up from 1 in 159 in 2010. COVID-19 has suppressed official numbers reported to be seeking international protection, stranding people internally and at border crossing, for example at Europe’s borders at Bruzgi while Glasgow’s 2021 COP26 was in session.

Climate change needs human rights principles and practices to evolve, if the right to life is to be protected, as a fundamental ‘right which should not be interpreted narrowly’, but widely enough to accommodate environmental problems. Thus Filippo Grandi, UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) suggested:

if you have an immediate threat to your life due to climate change, due to the climate emergency, and if you cross the border and go to another country, you should not be sent back because you would be at risk of your life, just like in a war or in a situation of persecution.’

Yet, it seems impossible to row back a system that locks in forced displacement and precarity, forcing migrants into situations of terrible danger. Pushback measures like using survival rafts to cast migrants adrift at sea represent no less than ‘torture by rescue’. Such appalling instances bring the entire ‘liberal’ international order of human rights, ‘development’ and security into question. The entire system of protection needs to be re-thought, reversing the inconsistency, fragmentation and inhumanity that currently characterizes it. New threats in the Anthropocene demand greater solidarity. Restrictive state borders leave refugees with little support, except from individuals and civil society groups responding to, and challenging, the inhumanity of bordering practices.

The ‘armed lifeboat’ necessitates critical historical reflection on legacies and continuities between authoritarian nationalism, colonialism-imperialism, racism, and environmentalism. Right wing ‘ecologism’ tries to convince ‘winners’ that cooperation is morally weak and economically impossible, insisting that only white Europeans, colonists and settlers have the privileges of rights, civilization, dignity and humanity. They imply that humanity must be dramatically denied to Others, authorizing ‘pushback chains’ to effect mass expulsion, dehumanization and death. Civil society and citizens who try act with solidarity have been criminalized.

Our era of ‘Great Derangement’ necessitates a creative response, in which human rights as an actual encounter between persons is not erased. Ethical creativity is required, to reverse the dehumanizing tendency to avoid, deter and deface the ethical encounter. Human rights has not been successfully ‘balanced’ against states’ objectives to borderize and repel. Collective security has not managed to change its referent object from protecting borders to protecting human beings. Human beings must extend rights and solidarity, beyond the exclusionary ‘armed lifeboat’.

Imagining human rights solidarity requires the development and protection of human ethical imagination and know-how. An alternative strategy of global solidarity must directly reverse the idea of securing ‘only one armed lifeboat’, at the cost of humanity, by violently pushing back the Othered humanity who were driven towards borders by environmental injustice and climate colonialism in the first place.

Getting beyond the inhumanity of the ‘armed lifeboat’ will require much ethical rethinking around greenhouse emissions and migration, but also much more than that. Our universalizing, yet exclusionary ‘armed lifeboats’ of economic, fiscal, political and juridical theories, assumptions and evidence must be challenged. New approaches, like Modern Migration Theory endorse migrant protection on non-negotiable human rights grounds, but are also beginning to challenge economic orthodoxy underpinning migrant deterrence, using new economic evidence to support less draconian policies.

The creation of solidarity requires ethical creativity, ethical imagination and ethical know-how to counter drifting international norms and dehumanization. Civil society, citizens, funders, polluters, and states must learn to collaborate and take practical action to nurture and foster human values and ethical forms of internationalism.

NOTES

*A version of this blog was first written as a mini-lecture for the ENLIGHT University consortium’s ‘Climate Change and Migration’ lecture series.

**[Square brackets indicate works that are unreferenced, to avoid citation].

Su-ming Khoo, Ph.D.

National University of Ireland Galway

ORCID: 0000-0001-8346-3913