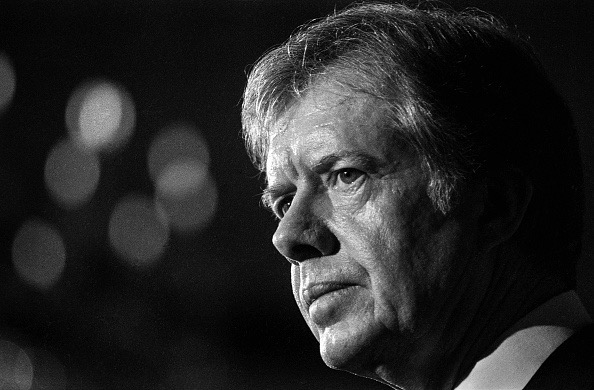

Morality in foreign policy: reflections on a remarkable gentleman from Plains, Georgia

It was June of 1979, and I was newly arrived in Kenya for what would become ten years working in and exploring that beautiful country. Being a little insecure in this new environment, I was cautious when a young Kenyan man approached me in Nairobi while I stood in the long queue awaiting entrance to the National Museum of Kenya. Still, his smile was disarmingly warm as he inquired if I were an American. After acknowledging my nationality, his next words astounded me.

“On behalf of all Kenyans, I would like to thank you.” Then, before I could gather my wits to think how to respond, he interjected: “No, not on behalf of all Kenyans…on behalf of all Africans! I thank you because you have a President who cares about our human rights!”

I cannot recall ever feeling prouder to be an American, and his generous words of gratitude have left me pondering the deep significance of human rights and human dignity ever since. Indeed, I would point to that moment as the origin of a career trajectory that would eventually lead me to become an ethicist and human rights activist who has now worked in 42 countries around the world. I will therefore take this opportunity to follow the example of that young Kenyan gentleman, and extend my gratitude to President Jimmy Carter. I’ll also acknowledge that President Carter, as a champion of human rights, has set a very high standard for me to work towards.

Even as he campaigned in 1976 for the presidency, Jimmy Carter clearly stated his intention that the United States must exercise moral leadership in the world, especially in the promotion of universal human rights and dignity. Upon taking office, President Carter moved quickly to place human rights at the center of his foreign policy, showing a determination in this context that had never been seen in the White House before. His strong moral stance was demanding; he held both allies and adversaries of the United States to account for their human rights failings, despite the tensions that this would bring to international relations. Of relevance to my previously mentioned Kenyan interlocutor, President Carter promptly suspended foreign aid to neighboring Uganda because of mass murders and other horrific human rights abuses carried out in that countryunder the rule (and often at the whim) of the dictator Idi Amin.

Carter’s record on holding countries accountable for human rights standards was not without inconsistencies. Due to the influence of some senior members of his administration who stressed other international relations priorities, his treatment of Iran, the Soviet Union, and some other egregious human rights abusing countries was more nuanced. Still, political opponents often attacked President Carter for his emphasis on human rights over what they asserted were more important American self-interests. In his successful 1980 presidential campaign against the then incumbent President Carter, Ronald Reagan asserted that Carter’s emphasis on human rights was dangerous. Reagan attributed what he viewed as the weakening of U.S. allies and strengthening of U.S. adversaries to Carter’s human rights policies, and many voters were swayed. A return to prioritizing human dignity and human rights would need to wait until President Obama and President Biden.

In moral terms, human rights are universal. For President Carter and for many of us, human rights serve as effective and measurable indicators of the recognition and respect for universal human dignity. President Carter took this universality principle seriously, balancing his foreign emphasis on human rights with many domestic achievements. This balance was evident in Carter’s improvements to social services and better access to quality public education. He established the Department of Education and strengthened the Social Security system. Carter also set new standards in the hiring of women and racial minority persons into the federal governmentworkforce, although extending that outreach at scale to include LGBTQI+ persons would need to wait until President Barack Obama, whose administration appointed me as the very first (and, sadly, still only) transgender appointee within the federal foreign affairs agencies (I served at USAID).

Diplomats implement foreign policy, and that is a discipline shaped by pragmatism and the need to defend the interests of the United States. Carter’s Secretary of State Cyrus Vance promised that the United States would draw attention to human rights concerns, but he qualified this by saying that this would occur only when it would be “constructive” to do so. Vance would further limit America’s focus on human rights to just three categories: freedom from government violation of personal integrity; the right to access basic needs (e.g., food, shelter, and education); and civil and political rights. And while Carter’s 1976 campaign was based on an explicitly moral approach to governance, once in office this was quickly translated by his administration into international laws and treaties intended to secure the desired outcomes. Shifting from a moral to an almost exclusively legal focus involved a tradeoff that entailed the loss of connection to much of the motivational power of the moral principles from which such laws and treaties had sprung. Nevertheless, President Carter’s 1978 Presidential Directive 30 provided the most robust and exacting standards of human rights promotions and protections this country had ever seen at that time.

The record of diplomatic and political action taken by the United States on human rights since the Carter administration has been inconsistent at best, but the current Biden administration has been both proactive and introspective in promoting universal human dignity and rights around the world while also acknowledging that America’s domestic record on human rights is far from ideal. Yet despite the uniquely moral position during the Carter presidency, the political need to justify a human rights stance on the basis not of morality but out of self-interest remains predominant, as evident in the words of our current Secretary of State, Andrew Blinken: “It is squarely in America’s national interests and strengthens our national security when democracy and human rights are protected and reinforced worldwide.”

Diplomats are not the same as development folks. Those of us who work in the sectors of humanitarian response and international development pursue an agenda that is different, if occasionally overlapping, to diplomacy. Instead of prioritizing national self-interest, we strive to facilitate the wellbeing, safety, opportunities, freedoms, universal dignity, and all human rights of all persons everywhere, especially in least developed countries, because that is what morality demands. Our agenda is best served by honoring the intersectionality and equal importance of all human rights: civil, political, economic, social, and cultural. Unfortunately, USAID has not adopted that rationale for a broader human rights development mandate, remaining with a human rights approach that is much too siloed, too legalistic, and focused much more on cataloging abuses of human rights than on the promotion of the moral meaning of universal human dignity.

While the debate on how best to pursue universal human dignity and rights will continue, this moment is particularly poignant. We are all now engaged in the process of bidding farewell to President Jimmy Carter, who has recently entered hospice care at his home in Plains, Georgia. This sobering moment offers us an important opportunity to reflect not only on the life and work of this remarkable leader, but also on the moral dimensions of humanitarian response and international development. We are called to reflect – right now – on how we ought best to strengthen and enrich our moral vocabulary and our understanding of applied ethics, to better achieve the effectiveness and meaning that such a moral commitmentdemands of us.

As noted earlier, I have found the inspiration for my career in applied ethics and the promotion of human dignity in President Carter’s own remarkable moral leadership. His caring example of humility, decency, unwavering moral conviction, and commitment to morally meaningful action has never abated since his time in the White House. Recently, I have been fortunate to see the Center for Values in International Development – which I founded and now lead – be engaged by The Carter Center to help that remarkable organization expand its highly regarded human rights focus to also include understanding and promoting the human rights of LGBTQI+ persons. During both my recent training visits to Atlanta and in all my engagements with The Carter Center, I have been moved by the sincerity, care, compassion, and commitment of the leadership and staff of that venerable institution.

Were The Carter Center the only legacy of President Jimmy Carter, that would be more than enough. Unsurprisingly, however, President Carter is leaving a deeper, wider, and extraordinarily profound moral legacy that ethicists like me will long take inspiration and guidance from.

On a personal level, I especially prize one quote from thisexemplary leader:

“I have one life and one chance to make it count for something… My faith demands that I do whatever I can, wherever I am, whenever I can, for as long as I can with whatever I have to try to make a difference.”

Moral leadership cannot be more eloquently expressed.

Photo: GettyImages